AI Tech parks

_If India wants to be a significant player in the AI space it will need to take a concerted effort to actively encourage investments into the space. The good news is that we have done this before. All we need to do is adapt our IT playbook to the AI age.

This is a link-enhanced version of an article that first appeared in the Mint. You can read the original here. If you would like to receive these articles in your inbox every week please consider subscribing by clicking on this link.

When I first heard of DeepSeek, my immediate reaction was one of disappointment. Everyone else was raving about the capabilities of the model and the frugality with which it had been trained, but I couldn’t get past the fact that China demonstrated the ‘jugaad’ I was expecting India to show. DeepSeek proves that it is possible for cutting-edge AI to emerge even under constraints, thanks to workarounds. For India, this should be as much a warning as an inspiration.

India’s IT Revolution

I am somewhat surprised to find ourselves in this position. After all, we have a reputation of being an IT powerhouse. In 1992, India’s software exports were just ₹52 crore. By 2022, that figure had exploded to ₹8.48 lakh crores—a 16,000-fold increase. Those of us who have been a part of this journey know that none of this was pure chance. India’s emergence as a global IT powerhouse is as much the result of deliberate policy choices.

Among these was the Software Technology Parks of India (STPI) scheme, a programme that offered IT businesses a suite of incentives. STPI units were eligible for a complete income tax exemption for ten consecutive years and could import hardware and software into the country completely duty-free. At a time when foreign ownership was severely restricted, 100% foreign direct investment was permitted in these companies through the automatic route. Most states set up single-window clearance facilities that radically simplified the process for availing these benefits.

Partly as a result of these measures, the IT industry’s share of total Indian exports grew from less than 4% in 1997-98 to around 25% in just 15 years. This cemented India’s position as the world’s IT services capital, so much so that when COVID forced global lockdowns, had it not been for the robust IT back-end that local outsourcing operations provided, much of the world’s critical IT infrastructure would have ground to a halt.

And Now AI?

All this should have translated into a significant advantage when digital technology made its next orbital shift. Unfortunately, success in one era is no guarantee of leadership in the next. Unlike China, India has not been able to contribute significantly to the AI ecosystem, either with benchmark AI models or frontier solutions, despite the best efforts of the IndiaAI mission in procuring GPUs, funding the development of indigenous large language models (LLMs) and setting up a platform for datasets and models.

We would do well to learn from the lessons of our past. The Indian IT revolution did not take place because the government procured the hardware that IT companies needed or made other resources available to them. All it did was to create appropriate market conditions that encouraged entrepreneurship so that businesses had the confidence to make the long-term investments needed to develop a successful tech industry.

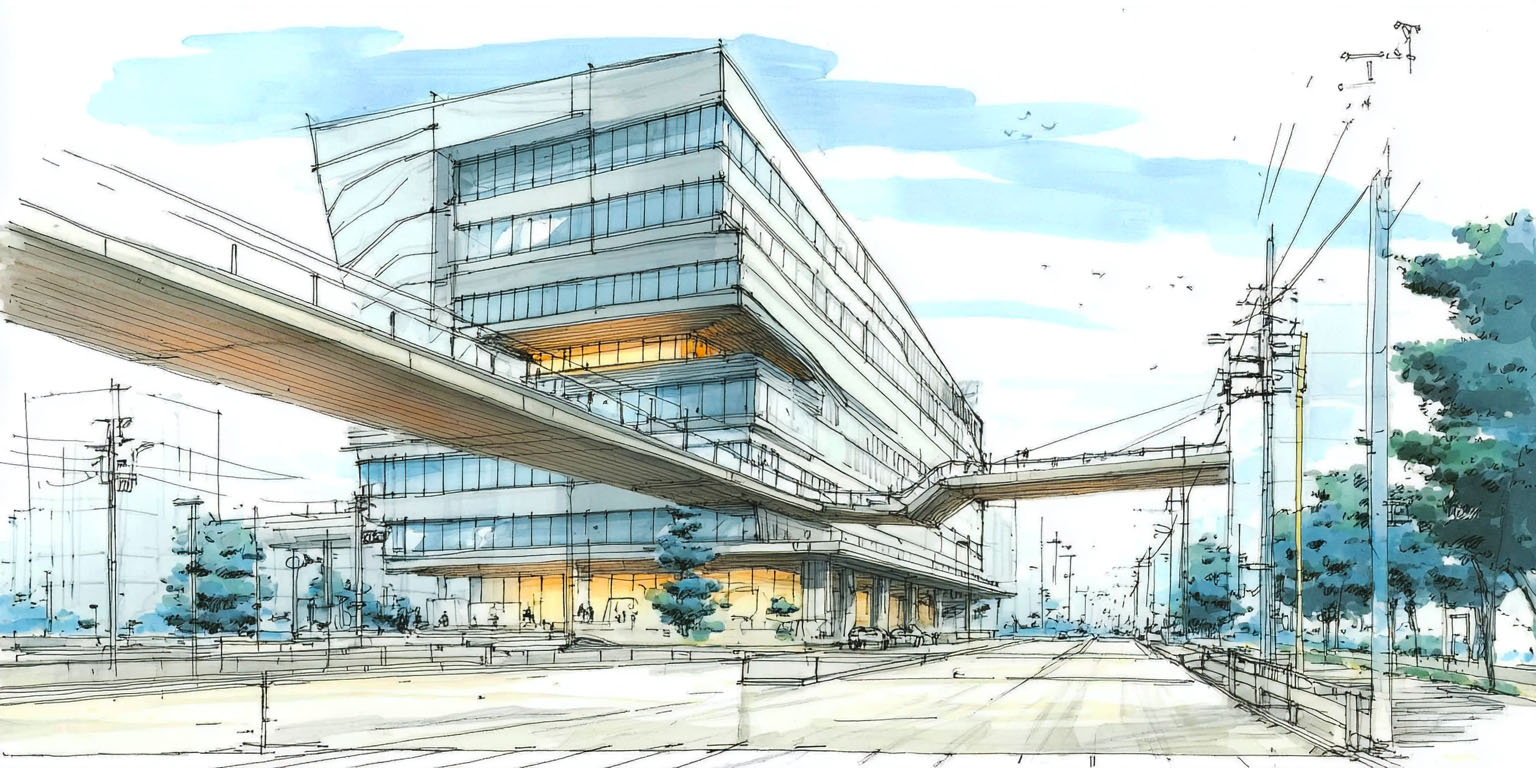

This is exactly what we should be doing to promote AI. Rather than procuring GPUs, the government should create incentives for private investments in the AI space. This could take the form of long-term tax holidays that will provide direct benefits to those investing in AI, as well as tax breaks for the procurement of all that it takes to build a successful AI business. Reliable power and high-quality bandwidth should be made available at scale, through dedicated AI parks that are strategically located near cable landing stations and adjacent to reliable power facilities.

The Right Signals

But above all, the government needs to send out a clear signal that it is ready and willing to take extraordinary measures to encourage AI innovation in India. One way in which it could do this would be to put in place a liability regime designed specifically for AI. Recognising the probabilistic and non-deterministic nature of AI, the government should announce that it will prefer remediation over punishment. Recognising that AI models are prone to errors, it should reassure AI companies that they will not be punished so long as they take steps to quickly fix what went wrong.

Equally important is the need to put in place an AI-friendly intellectual property and data protection regime—one that gives entrepreneurs the confidence to train models in India using Indian datasets without the fear of being sued for copyright infringement or data protection violations. It should be possible to design appropriate frameworks that can protect the interests of creators and data principals that, at the same time, give AI companies adequate comfort.

Once the Centre puts in place these key strategic incentives, state governments will compete among themselves to attract investments. During the IT boom of the 1990s, states like Karnataka and Telangana competed with each other for investments by offering subsidised land, power guarantees and data centre facilities, while offering single-window clearance regimes managed by dedicated commissioners. We should be able to re-create that sort of positive energy around AI.

The IT boom of the 1990s came about not because the government got into the business of IT services, but because it had the courage to carve out a favourable regulatory environment—one that gave entrepreneurs the assurance that their investments would be protected and treated them as partners in national development.

We need to do the same for AI and do it soon. If India does not seize this moment, we risk forever being users, not builders.

We already have the playbook. All we need to do is apply it.